The Third Current: How Black Jacksonville Shapes the River's Flow

Vol. 1, Issue 8 | March 31-April 6, 2025

CURATOR’S NOTE

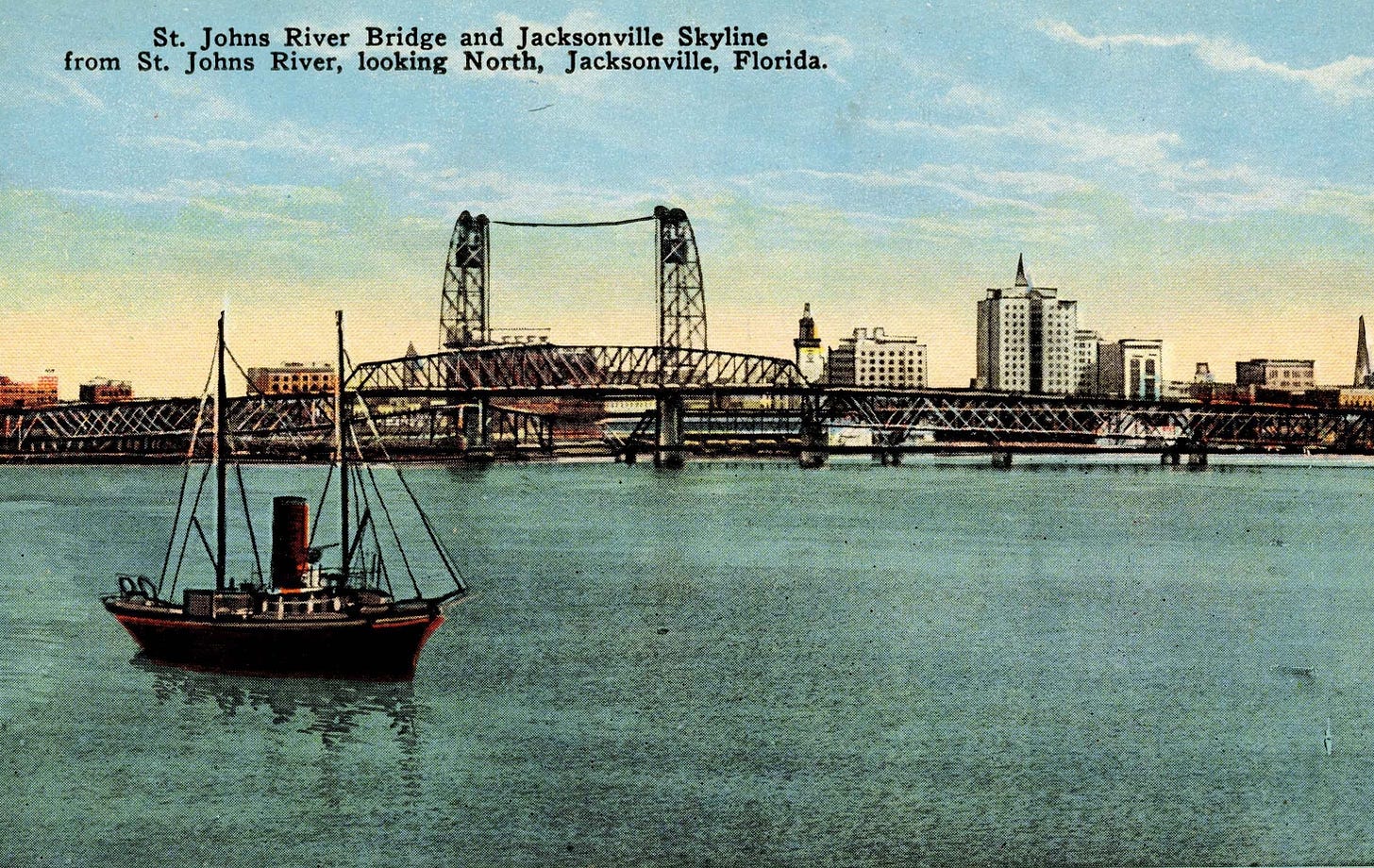

My first breath was drawn at Baptist Medical Center where the St. Johns River bends. I've been told the details so often they've become a kind of inheritance. They say I arrived when winter still held the city in its grip, when the river ran dark and deep beneath a steel-gray sky, when shrimp boats huddled against their moorings before their slow procession toward the Atlantic. Memory has a shape, and mine begins here—where fresh water yields to salt, where the river flows north, where every curve holds stories as ancient as the Timucua and as recent as yesterday's rain.

I always knew the river was near. Our elementary school alma mater began, "Near the banks of the St. Johns River stands a school so fine…" And in those early years, I took those words to heart, believing the river was not just a body of water, but a kind of marker, a living, breathing presence. The fluorescent lights would flicker sometimes during afternoon thunderstorms, and our music teacher would pause at the piano, her fingers hovering above the keys as we waited for the power to steady itself. In those suspended moments, I imagined I could hear the river rising, claiming its place in our curriculum, insisting on being acknowledged in the marrow of our education, 310 miles of liquid history moving through Florida's varied landscapes, each bend a layer of time, each current carrying fragments of voice and silence.

I didn't realize then how intertwined my story was with the river's, how many other stories were built on the strength of people who had shaped this city long before I arrived. But in my mind, I understood early that the river’s presence was a living entity, a constant in the narratives of those who came before me, those who shaped this place and those who would come after. When I hear the opening line of that old school song, I'm reminded again. This river doesn't just flow north, it bends, it shifts, it carves new paths. And so do we.

The first time I truly heard "Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing," it was a baptism of sound in Bethel Baptist Institutional Church’s historic sanctuary. I sat in the pew beside my mother, admittedly more concerned with the length of the service than its significance. Roland Carter's arrangement moved through the space like spirit made audible—Henry Mack’s hands drawing centuries of prayer from ancient pipes, DeLando Williams coaxing thunder and whispers from ebony and ivory. Professor Leonard Bowie shaped the brass section's breath into perfect form. Each note became a thread in a tapestry of praise. The choir became a river of witness—Jerald DeSue’s tenor as rich and powerful as ancestral memory, Helen Wright’s contralto as beautiful as morning light through stained glass. Reverend Rudolph W. McKissick, Sr. stood in the pulpit like a conductor of history itself, while Padrica Mendez sat at the edge of the left front pew and saw past sanctuary walls to distant European stages where her voice had once made angels weep. I sat up taller, feeling something ancient and new simultaneously rising within me because what began in a Jacksonville schoolyard in 1900 had become more than an anthem. It was (and is) a guide to survival, each note a bridge between what was and what is possible.

Religious institutions like Bethel, Mount Olive AME Church and First Baptist Church of Oakland had long been anchors for my family, an ever-present force that tethered us to history, community, faith. It was here, in the quiet of sacred space, that I first learned the art of storytelling, of holding the past in a way that made it not just a relic, but a living, breathing force that shaped our present. I later found this practice of preserving what was sacred, and what was often overlooked, in the work of storytellers like Zora Neale Hurston, whose pen became both witness and translator for a history rarely seen. When Hurston stood in a Live Oak courtroom reporting the Ruby McCollum trial in 1952, she wasn't merely recording testimony. She was uncovering buried truths—revealing the hidden structures of power, tracing the invisible patterns that shape human stories. Her reporting didn't just document a court case; it exposed the unwritten laws that governed Black life in the mid-20th century American South.

This act of uncovering was also what filmmakers at Norman Studios were doing; where they weren't just producing movies but were creating new ways to show Black humanity—their stories so sophisticated that Hollywood would need decades to understand their revolutionary meaning. The old buildings still stand, their windows reflecting sunsets the same way they did a century ago, each pane of glass a window into what was possible, what remains possible.

Just as Norman Studios challenged mainstream portrayals by centering Black life on screen, Black radio carved out a space where voices that had been marginalized elsewhere could not just be heard, but could shape the cultural conversation itself. These sounds still pulse through our city’s veins. From Ken Knight’s voice carving pathways of community through radio waves, to the bass notes that yet vibrate through the floors at the Ritz Theatre. DJs and announcers created invisible networks of support, carrying news, music, and hope across social boundaries. I think of sitting in my mother's car outside the Winn-Dixie on Edgewood, waiting for a summer storm to pass, as WPDQ’s host wrapped their voice around us like a familiar blanket, making the rain-streaked windows feel less like confinement and more like a cocoon.

This publication, much like the river, is both a reflection of the past and a guide to the future, a conduit for the voices and stories that refuse to be drowned. We’ve grown, we’ve shifted, and now, we, too, carve new paths.

Jacksonville is home to nearly one million people, and Black residents make up 30% of the population. But numbers alone don’t capture our presence. We are architects of culture, builders of community, and keepers of stories that define this city—not just in the ways history remembers, but in the ways it chooses to forget. Behind the statistics are Sunday gatherings where three generations move to the same rhythm, weekday mornings where history is served with breakfast, midnight conversations where tomorrow is always being born.

Jacksonville’s pulse is uniquely shaped by Black creativity. It is a story told not in percentages but in the city’s very rhythms and blueprints. In musical composition, the third is what transforms a chord from flat suggestion to rich resonance. It creates the harmony, the complexity, the depth. A major third rises with hopeful brightness; a minor third descends into emotional richness, holding generational memories. Without the third, music remains mere proposition; potential without profound expression.

We began two months ago as 33 ⅓: Black Arts and Culture Chronicle, a name that spoke to our technical precision. But names evolve, as rivers do, finding truer courses. We are now The Black Third, a designation that speaks to musical harmony, to the creative space between margins, to the essential rhythm that completes a city’s cultural composition and carries stories outward, like a river finding inevitable passage to the sea.

The reach of our publication now extends far beyond Duval County’s 762.6 square miles. Forty-five percent of our readers live outside Florida, spread across 20 states and eight countries, showing how well-told local stories resonate as universal human experiences.

Like the St. Johns itself, we flow north. Against expectation, against what others insist is the natural order. We move as rivers have always moved, finding paths of necessary resistance, carrying within our current centuries of voices and vision, struggle and celebration, memories and music. This is not simply a publication; this is a continuation. It is the river that witnessed my first breath speaking through new channels, still flowing, still bending, still defying what others say is possible.

—Khalilah L. Liptrot

Curator, The Black Third

ONGOING EXHIBITIONS

Venus, In Healing: Recent Works by Tatiana Kitchen

Yellow House Art Gallery | Through April 12, 2025

"Venus, In Healing," a transformative solo exhibition by Tatiana Kitchen masterfully interweaves imagery of Black women with the land and cosmos. Through her evocative compositions, Kitchen draws parallels between the planet Venus and the sacred experiences of motherhood, inviting viewers into a deeply personal narrative of resilience and metamorphosis. Her work positions nature not as mere backdrop but as a vital force of restoration, offering a transcendental meditation on feminine power and spiritual rebirth.

Access:

Wednesday, 12 PM-7 PM

Saturday, 11 AM-2 PM

Location: 577 King Street

Contact: (904) 419-9180

Jacksonville’s Norman Studios: Movie Posters from the Permanent Collection

Cummer Museum of Arts & Gardens | Through December 6, 2026

Before Hollywood's rise, Florida was a hub for the early film industry, thanks to its favorable conditions. In the 1920s, Jacksonville native Richard Norman seized this opportunity, producing films featuring Black casts and protagonists that boldly challenged the status quo. Norman's innovative studio complex, now a historic landmark, stands as a testament to his trailblazing contributions to American cinema.

Access:

The museum opens at 12 PM Sunday

The museum is open until 9 PM Tuesday

Wednesday-Saturday, 11 AM-4 PM

Location: 829 Riverside Avenue

Contact: (904) 356-6857

The Museum Space

A.L. Lewis Museum at American Beach

The A.L. Lewis Museum showcases both permanent and rotating exhibits highlighting African American culture, history, and civil rights. Visitors can explore artifacts, photographs, and documents that illuminate the local community's profound influence on American history. Guided tours are highly recommended for a deeper understanding of the exhibits and the history they represent.

Access:

Friday-Saturday, 10 AM-2 PM

Sunday, 1 PM-5 PM

Visitors are encouraged to check the museum's website or call ahead for any schedule changes

Location: 1600 Julia St, American Beach

Contact: (904) 510-7036

The Road to Black History Runs Through Lincolnville

Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center

Step into over 450 years of history at the Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center, located within the heart of St. Augustine's historic Lincolnville District—once home to a community of freedmen who shaped the city's cultural landscape after the Civil War. Here, the rich story of Black history in Florida unfolds, from the ancient empires of West Africa to the early Black presence in colonial Florida, through to the powerful movements of the 20th century.

The museum guides visitors through the lives of free and enslaved individuals from the Spanish colonial period to the tireless activists of the Civil Rights era, revealing how the resilience and contributions of Black Americans have left an indelible mark on the fabric of the state and nation.

Access:

Sunday-Monday, 1 PM-4:30 PM

Tuesday-Saturday, 10:30 AM-4:30 PM

Location: 102 M. L. King Avenue, St. Augustine

Contact: (904) 824-1191

Lift Ev’ry Voice

Ritz Theatre & Museum

Discover the story behind "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing," the beloved anthem composed by Jacksonville natives James Weldon and John Rosamond Johnson. Step into the vibrant "Harlem of the South" nightlife captured by photographer Ellie L. Weems. Experience the quiet resolve of Civil Rights protesters at a Woolworth's sit-in. These immersive encounters at the Ritz Museum connect you to the rich tapestry of Jacksonville's African American history and heritage.

Access:

Tuesday-Friday, 10 AM-4 PM (tickets must be purchased by 3 PM)

The museum is open until 8 PM Thursday

Location: 829 North Davis Street

Contact: (904) 632-5555

Eartha M. M. White Historical Museum and Gardens

Clara White Mission

The Eartha M. M. White Historical Museum and Gardens celebrates the legacy of Dr. Eartha White and her mother, Clara English White, two African American women who dedicated their lives to community service. Located in the historic Globe Theatre in LaVilla, the museum showcases Eartha White's lifelong work to empower underserved communities, featuring portraits, personal memorabilia, and artifacts from her numerous initiatives. The museum continues Dr. White's vision by preserving and sharing Black history and culture.

Access:

Location: 613 W. Ashley Street

Contact: (904) 354-4162

Works on Paper

Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens

The Cummer Museum's collection of works on paper and photographs numbers approximately 2,200 objects, nearly a quarter of which are part of the Cornelia Morse Carithers Print Collection. Featuring works by celebrated artists, the collection includes the powerful visual narrative of Jacob Lawrence's The Migrants Cast their Ballots (1974).

Access:

The museum opens at 12 PM Sunday

The museum is open until 9 PM Tuesday

Wednesday-Saturday, 11 AM-4 PM

Location: 829 Riverside Avenue

Contact: (904) 356-6857

COMMUNITY SUBMISSIONS

Share details of your upcoming events here.

Deadline: Wednesdays at 5 PM

Todays edition brought memories to light. Thank you for continuing to share the rich history of Jacksonville from your lens while honoring our history. I look forward to embracing more from The Black Third!

I was so very curious as well as concerned to why the named changed thinking that the content may go along with it. Thank you for proving me wrong, and I look forward to the next jouney along with the waves of the river. Your storytelling always creates a visual storyboard of images for the reader. Keep them coming.